Housing studies and needs assessments are often built around long-term growth projections provided by MPO or state authorities. These estimates consider factors like employment, household formation, and migration at regional, state, or even national scales. Local housing plans typically take their slice of this larger pie as the primary input for calculations of future housing need and the housing production they should plan for to accommodate it.

On the surface, this seems like a perfectly reasonable approach. However, there are some important variables and considerations missing from the calculus. Most importantly, in many places, significant new growth is not possible without changes in policy and regulation, such as upgraded infrastructure or updated zoning. This is especially true in places that are largely “built out” and where the only way to add more housing is to redevelop existing structures into higher density housing, often only allowed through changes to zoning. Major public investments and regulatory changes require due process and resident support. In the event these interventions run counter to the community’s vision for its future, they may not be made and the projected growth may not be possible.

While long-term projections may suggest demand is strong and growth is inevitable, often the only way to realize this change is through municipal action with public support. As such, to be useful for practical planning purposes, growth projections should be filtered through local discourse and policy lenses before they can be applied to a planning process as a reliable indicator of the future trajectory. How does the community want to grow? What are its values and goals relative to affordable housing? Answers to questions like these help channel raw projections into actionable planning inputs.

Breaking down housing demand for more targeted planning

Especially when applied at the local level, housing demand is more nuanced than growth projections might suggest. There are multiple sources of demand to respond to, both from within and from outside the community. And responses to different sources of demand require different policy considerations and mechanisms. Depending on local housing goals and objectives, demand could be characterized as one or a blend of the following:

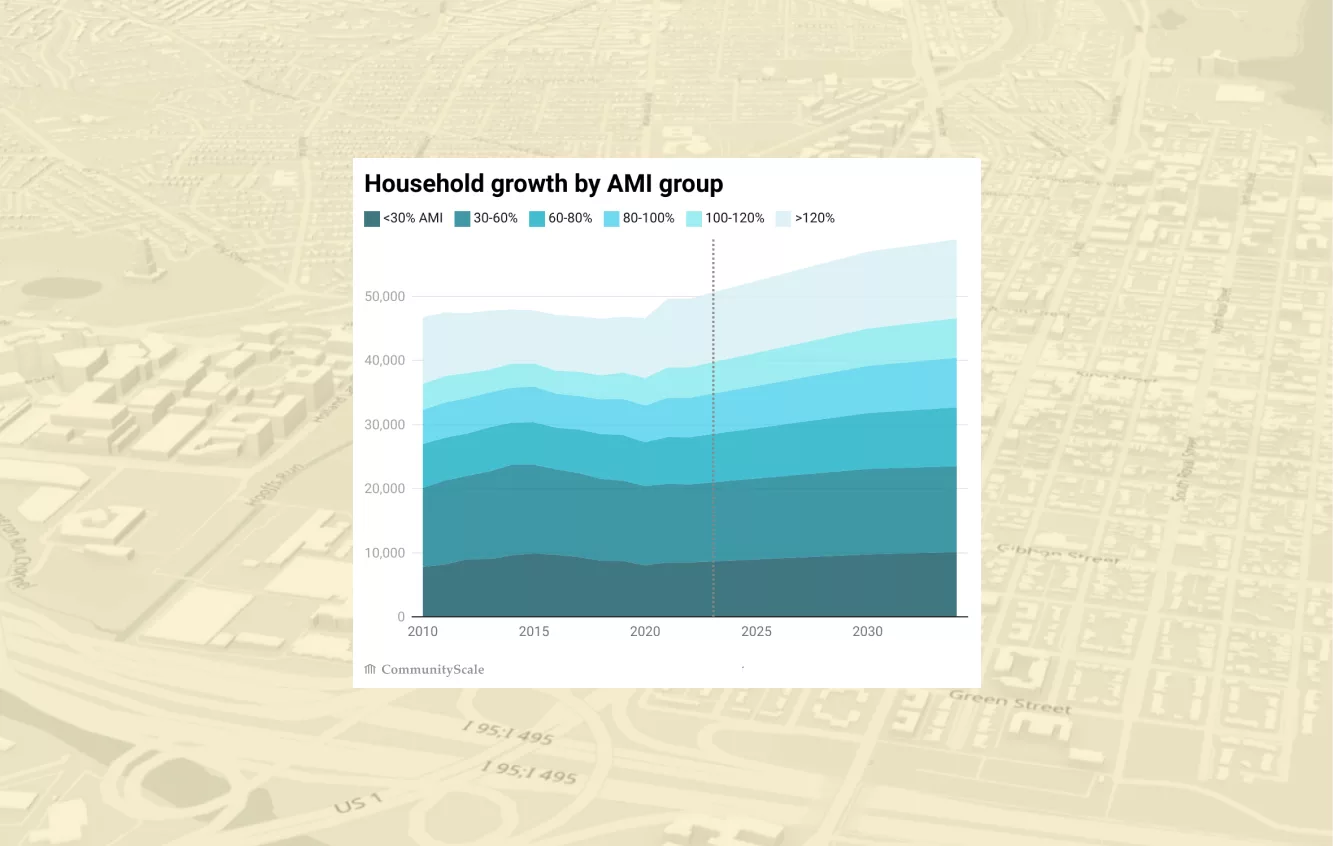

- Organic growth as informed by current projections and potentially modified by knowledge of shifting demographic and market trends that may influence future growth and population change.

- Regional market demand capture as determined by migration patterns and market preferences at metro and broader scales.

- Affordability need as established by the local distribution of cost burdened households and the units they need in terms of size, type, and cost.

To help inform the planning process, we at CommmunityScale work with our clients to translate these three demand channels into three questions which directly inform how we model growth and change to inform their housing plans:

- Growth goal: How much growth is desirable over the next 10 years?

- Avoid further growth

- Accommodate slowed or targeted growth only

- Maintain organic growth trends

- Accelerate growth somewhat

- Accelerate growth significantly

- Other approach?

- Attainability goal: How should the community manage its supply of affordable housing as a component of new growth and development?

- Avoid increasing attainability gaps

- Reduce attainability gaps somewhat

- Reduce attainability gaps significantly

- Other approach?

- Land use goal: How much should existing land use patterns change to accommodate new growth and development?

- Maintain current mix of housing types

- Accommodate low and moderate density new housing types

- Accommodate all new housing types

- Other approach?

Based on the community’s response to these questions, we can calibrate how we model future housing needs and production targets to optimize for its preferred future outcome. In turn, this exercise influences how policy should be shaped to enable the growth, attainability, and land use mix envisioned by the community.

There are so many ways a community can control how it grows and changes (or doesn’t). Planners must seriously consider the policies (and politics) under the hood and incorporate this into how they understand, project, and position for their communities’ potential future.